By Brian Lowther

Today, I continue my series exploring six common human desires and why God instilled them into us. You can read the first two installments here: The Desire for Survival and Pleasure, and The Desire for Power. As I noted in those two posts, I’m writing from the assumption that our desires at their roots are good and programmed into us by God for a good reason. Specifically, I think his reason is to help us participate with him in bringing his kingdom on earth as it is in heaven, which is essentially a battle against darkness and evil.

Creativity

Beyond survival, pleasure and power, I have a desire to express creativity. I like to think of myself as a creative person. That is, I’m a comically bad dancer and I may be the least musical person in the Western Hemisphere. But besides these embarrassing shortcomings, I get a lot of satisfaction out of many creative pursuits, like drawing or writing.

This is usually where our definition of creativity stops, with artists, writers and entertainers. Because of this many people don't feel like they are very creative. But perhaps creativity is broader.

When God first created the world in Genesis, we are told that the earth was “formless and void.” This phrase has always brought to my mind a planet-sized glob of mush floating among the stars. But God apparently saw something in this glob of mush. In Michaelangelo’s words, “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” This may be what went through God’s mind as he fashioned our planet.

I think of this process as bringing order out of chaos. That is my preferred definition of creativity. Apply this definition to any masterpiece—be it visual or performing art, architecture or literature—and it holds true. This definition also fits the work an accountant does to make sense of someone’s taxes, or the work a parent does in raising children, those formless globs of mush.

Chaos

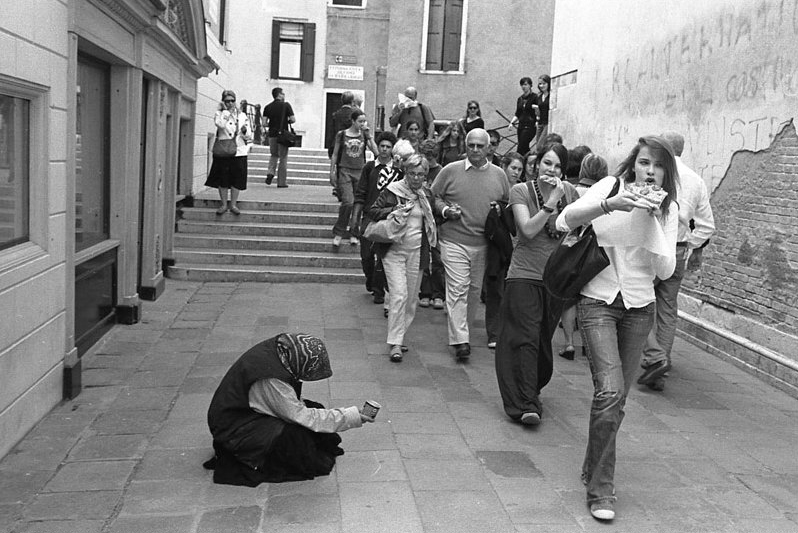

Interestingly, in the RWI view our planet wasn’t initially a glob of mush. It didn’t begin that way. It was good at its inception, but something went wrong. It became a glob of mush as a result of a cosmic war between God and Satan. The common Biblical phrase “formless and void” can also be translated, “destroyed and desolate,” as a battlefield after a great war. That is the world into which Adam and Eve were placed, a world at war.

But what is this war exactly? It is a subject of lingering confusion. Once while discussing the war with a friend, he very astutely asked, “But how do you fight a war against Satan?” It’s not like we can fire a nuclear missile at him.

I didn’t have an answer for him then. But now I would say, “I think the war is about Satan creating chaos. We can speculate that he creates chaos at the micro level through gene mutations; he creates chaos at the human level by destroying relationships; chaos at the spiritual level by choking faith; and chaos at the macro level through floods, earthquakes, etc. At the same time, God is at work bringing order out of all this chaos, bringing good out of evil, and he invites our participation.”

Why Did God Give Us the Desire for Creativity?

As with the other desires I’ve explored in this series, I believe God instilled this desire in many of us because we would need it to battle evil, to bring order out of chaos, to address major problems like spiritual darkness, disease and natural disasters. These things require great ingenuity.

God’s goal and pleasure seems to be bringing order out of chaos in the context of relationship and teamwork with us. When you ask a creative person how they did something, they often say, “I don't know. The idea just came to me.” My best ideas always come while waiting at a stoplight, or while mowing the lawn or while taking a shower, evidence that perhaps these ideas aren’t mine alone. These epiphanies come when my mind is quiet on account of being occupied by some routine or meditative task. Is this mental quietness necessary in order to hear God’s “still, small voice?” (1 Kings 19:12) I suspect so.

Self Worth

One last thing I find most interesting about the desire for creativity is—as with my desire for power—it’s not so much about the beautiful masterpiece I can create, or the problem I can solve. While there is satisfaction in those things, the much greater satisfaction comes when someone recognizes my creation or solution as elegant, sublime, valuable, etc. “If I create or achieve something worthwhile,” my internal monologue goes, “people will ascribe worth to me. If others ascribe worth to me, then I can have self worth.” That’s at the root of the desire for creativity. The deeper motivation is self worth. I’ll explore this desire for self worth a bit more in a subsequent entry.

Photo Credit: girl_onthe_les/Flickr

Brian Lowther is the Director of the Roberta Winter Institute