A Hunch and a Hypothesis

In the Roberta Winter Institute we’ve held a hunch and a hypothesis for quite a while that might just be completely mistaken.

First, the Hunch

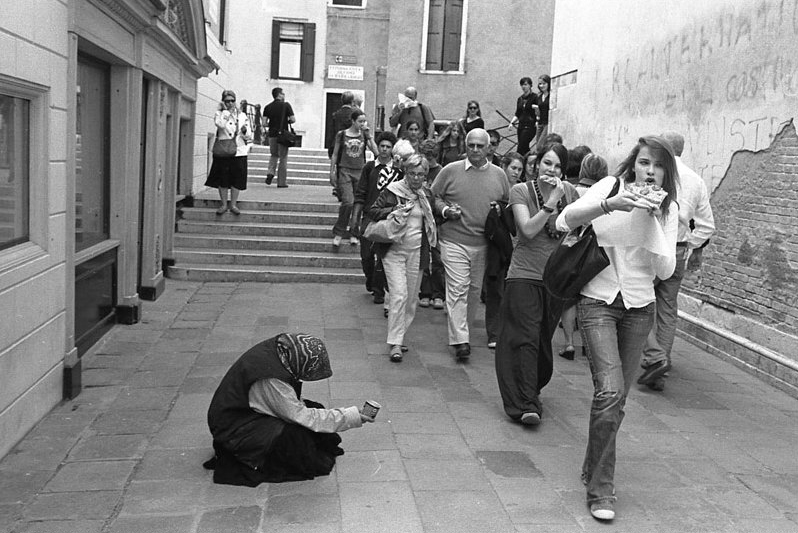

Our hunch is that the good works of believers attract people to faith in God.

Shortly before his death, Ralph Winter wrote an essay entitled, The Future of Evangelicals, which appeared in the book MissionShift: Global Mission Issues in the Third Millennium. In this essay he wrote:

…the usual way in which individuals come to faith is primarily by viewing the good works of those who already have faith—that is, by seeing good works that reflect the power and character of God.

Then a little later in the same essay he wrote,

… in order for people to hear and respond to an offer of personal salvation…it is paramount for them to witness the glory of God in believers’ lives—seeing the love and goodness in their lives and deeds, and their changed motives and new intentions. That is the reality which gives them reason to turn away from all evil and against all evil as they seek to be closer to that kind of God and His will in this world.

Is this true?

Do the good works of believers cause people to seek to be closer to God? Many passages seem to suggest as much. Matthew 5:16 comes to mind. “Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father in heaven.” Other examples include Mt 15:30-31, Mk 2:12, Lk 5:26; 17:11-16;18:43, Jn 20:30-31.

A historical example comes to mind as well. John Wesley was on board a ship bound for America in 1736. A group of Moravians were also aboard the ship. Over the course of the voyage Wesley came to admire the Moravians’ humility and meekness. One day a life-threatening storm occurred. Waves nearly engulfed the ship and the main mast split into pieces. Everyone screamed out in terror—everyone except the Moravians. The depth of their faith was apparently such that they quietly prayed and sang hymns in the midst of the storm. Wesley took note of that.

How about you?

Did a believer’s good works or admirable character attract you to faith in God?

- Was it their personal character (love and goodness in their words and conduct)?

- Was it a transformation (change in motives and behavior)?

- Was it their good works (generosity or helping the poor, the sick, orphans, widows, etc.)?

- Or was it something else completely?

In my own story, it was the transformation I witnessed in my father. My dad was a drinker and smoker since his early teens, and a life-long agnostic. He came to faith when he was 44-years-old and immediately quit smoking and drinking, stopped going to bars on the weekend, started treating my mom, my siblings and me differently. It was the epitome of a 180-degree change, a complete reversal in thinking and behavior. It had such a powerful impact on me that within three months—on the day after my 18th birthday—I started following Jesus in a very serious way and have never looked back.

Now, the Hypothesis

Our hypothesis is that innumerable numbers of people would come to faith in Jesus (i.e., evangelism and discipleship would become profoundly more effective and fruitful) if the body of Christ marshaled its resources and significantly helped eradicate the next disease.

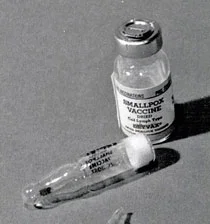

This hypothesis comes partly from something Ralph Winter often said, “Historically, the mission enterprise more than any other thing has fallen on the heels of the impact of medical missions.” And it comes partly from the results of the eradication of smallpox in 1979.

In his book Viruses, Plagues and History, author Michael Oldstone called the eradication of smallpox, “one of the greatest accomplishments undertaken and performed for the benefit of mankind anywhere or at any time.” What would be said and believed about Jesus if his followers teamed-up to eradicate the next major disease, let’s say malaria, or AIDS?

Let’s say a bunch of churches, denominations, mission agencies, philanthropists, Christian universities, etc., committed massive amounts of funding, human resources, and collective resolve and together formed the International Coalition for the Eradication of Malaria (for example). How much more would God be glorified if it were clear that it was done for that very reason? I think it would be talked about by nearly every thinking person in the world and in the pages of every newspaper and website.

But, is this true? And if so, would it affect the fruitfulness of evangelism, discipleship, missions, and church-planting?

There exists a fairly similar example right under our noses. The Rotarians have been at the forefront of the Polio Eradication Campaign since its inception in the mid 1980’s. Since that time they’ve contributed countless volunteer hours and over a billion dollars in funding, resulting in a 99% decrease in cases of polio worldwide.

Yet, even though I’m very passionate about the cause of disease eradication, I don’t have a burning desire to join the Rotary Club.

Do you?

Testing Our Hypothesis

I’ve thought about why, and—as embarrassing as this is to admit—I’ve decided it is because polio hasn’t affected me personally.

So, I wondered, what if the Rotary Club had eradicated a disease that affected me personally? Then would I join?

That disease would undoubtedly be pancreatic cancer, which took my beloved grandfather fifteen years ago. It’s the same disease that took Michael Landon, Luciano Pavorotti, and Patrick Swayze. Let’s say—prior to when my grandfather was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer—the Rotary Club set out to eradicate it, and they largely succeeded. If those circumstances were in place, would I be a member of the Rotary Club today?

Would you, if it were a disease that had affected you very personally? Would you donate money? Would you participate in any of their activities or fundraisers? Would you pray about their efforts?

I would. But I don’t think I’d join a local club.

Why Not?

I think it’s because I don’t have a close, personal relationship with anyone in the Rotary Club.

According to Rodney Stark in The Rise of Christianity, people come to faith not because of good works, or doctrine, but because of the faith of multiple people they trust. He says that people overwhelmingly come to faith as a result of relationships.

To quote mission researcher Justin Long, “If a person does not have a relationship with a believer–in fact, several relationships with several believers whom they respect–they will likely not [come to faith].” [1]

This holds true in my story. It wasn’t just because of my dad’s transformation. It was also because of my relationships with my Uncle Mark, my Uncle Mike and my friend Will. All these men were my elders. I respected them. I liked them. It was inevitable.

So much for our hypothesis.

But wait just a minute. Even though something as far-reaching and world-changing as the Rotary Club eradicating pancreatic cancer wouldn’t have caused me to join the Rotary Club, it would have had an impact on me. It would have said something to me about the Rotary Club. It would have resulted in a secret admiration in me for them because of the great service they had done for not only my grandfather and me, but all of mankind. I may have sought out friendships with them.

And given Rodney Stark’s research, if those friendships developed to the point that I knew multiple people in the Rotary Club whom I respected, I probably would have joined the Rotary Club. Think about it. If your three closest friends/mentors were part of the Rotary Club, wouldn’t you be inclined to become a member?